TL;DR: Jointly optimising hyperparameters and reward shapes in RL outperforms separate tuning, delivering better performance and stability, even in complex environments like Robosuite Wipe. No hand-tuning required!

Optimising Smarter: Joint Optimisation of RL Hyperparameters and Reward Shape

RL has achieved remarkable advancements, but one basic challenge remains ever-present: tuning hyperparameters and reward functions. This is tedious yet critical and can determine the success or failure of an RL algorithm. Traditionally, these two components are optimised independently, and in benchmark environments, reward functions are often left untuned altogether. This raises the question: is the tuning of hyperparameters and reward shapes truly independent?

In our work, Combining Automated Optimisation of Hyperparameters and Reward Shape (Dierkes et al. 2024), we demonstrated that they actually are dependent and achieving optimal RL performance requires tuning both components together. This challenges the conventional approaches and calls for more unified optimisation frameworks.

Interdependency between Hyperparameters and Reward Parameters

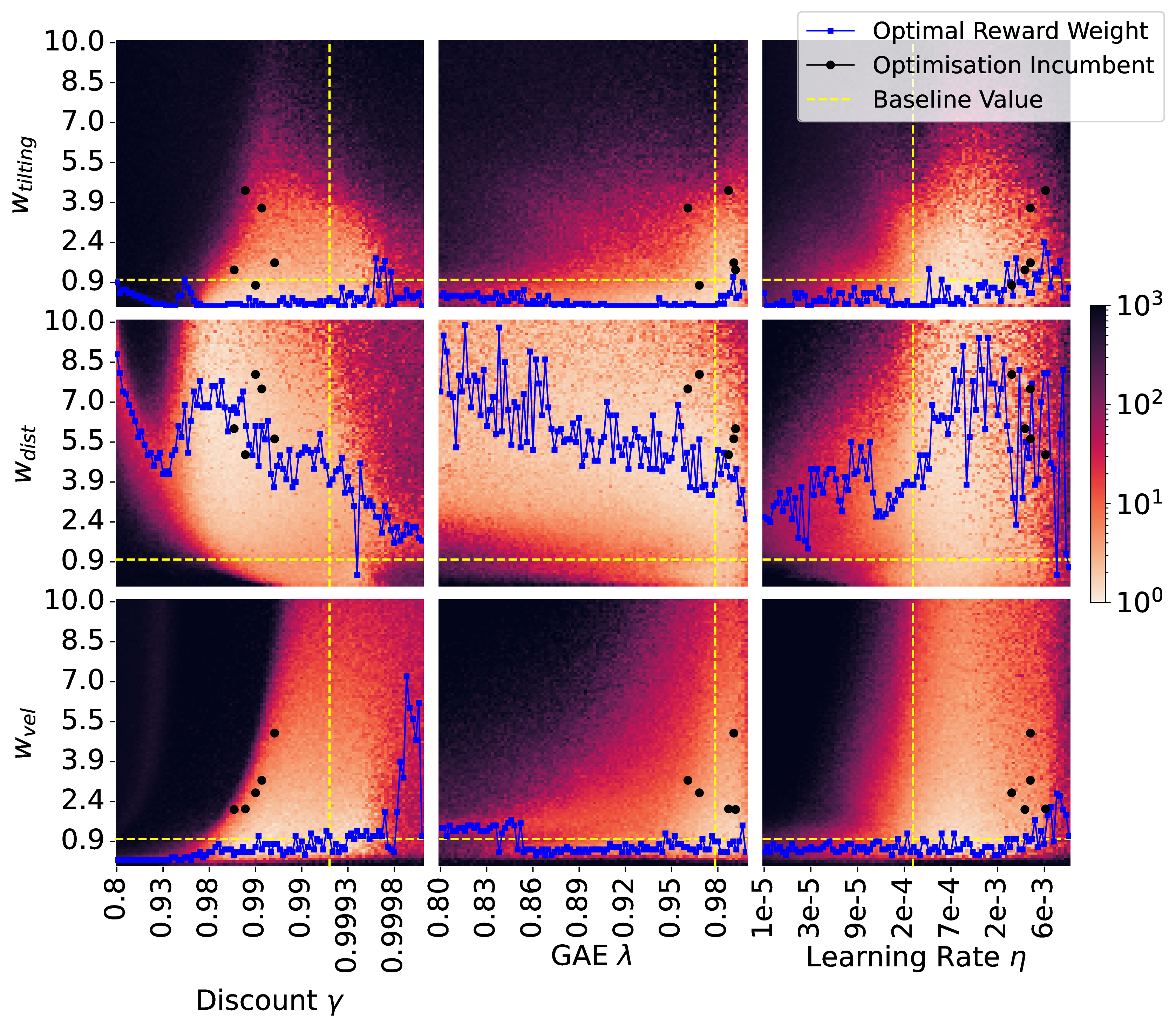

To better understand the interdependence of hyperparameters and reward shapes, we conducted experiments training the PPO algorithm on LunarLander. Specifically, we performed an exhaustive grid search over various hyperparameter values and reward weights in the reward function, analysing how each pair influenced training performance.

These findings are visualised in Figure 1, depicting the complex relationships between hyperparameters and reward weights. For instance, the distance weight reveals a non-convex region where successful training parameters emerge and further, performance can vary across the whole search space. Meanwhile, the velocity weights can have sharp boundaries that clearly separate regions of success from complete failure, showing the balance required for effective tuning. While our analysis was limited to pairwise combinations, it is reasonable to expect even stronger dependencies in higher-dimensional parameter spaces.

Hyperparameters and reward weights are therefore intricately linked, and their joint optimisation is important for achieving the best possible performance in RL applications. Independent optimisation approaches fail to capture these interdependencies, leaving potential performance gains unexplored.

Joint Optimisation in Practice

Recognising these interdependencies, the next step was to design a practical optimisation approach. Our goal was to examine a method that could seamlessly integrate with existing black-box hyperparameter optimisation workflows while jointly optimising reward weights.

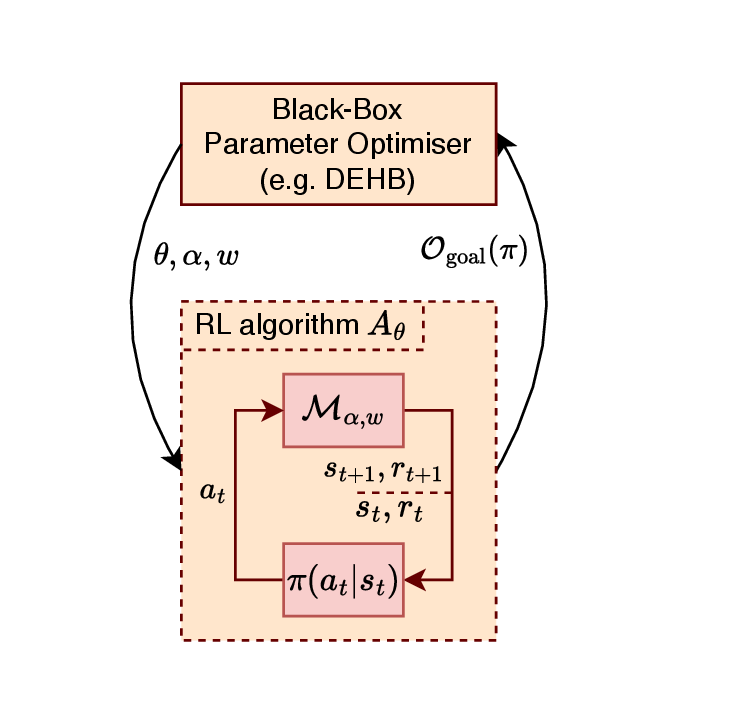

Figure 2 provides an overview of our optimisation loop. In this framework:

- Both hyperparameters \(\theta\) of the RL algorithm as well as scale \(\alpha\) and weights \(w\) of the reward shape are treated as part of a unified search space.

- The optimisation algorithm evaluates configurations by training the RL agent with hyperparameters \(\theta\) on the reward shaped environment \(\mathcal{M}_{\alpha, w}\). The it measures its external task performance \(\mathcal{O}_{\text{goal}}(\pi)\), a simple and sparse objective function to measure final policy performance (e.g. time of a successful landing in LunarLander).

- Promising configurations are iteratively refined, enabling joint optimisation of both components.

We used the DEHB (Differential Evolution with Hyperband, Noor et al. 2021) algorithm for this purpose, a state-of-the-art multi-fidelity black-box optimiser. However, the approach is general and can be easily applied to other black-box optimisation methods (e.g. SMAC or Optuna).

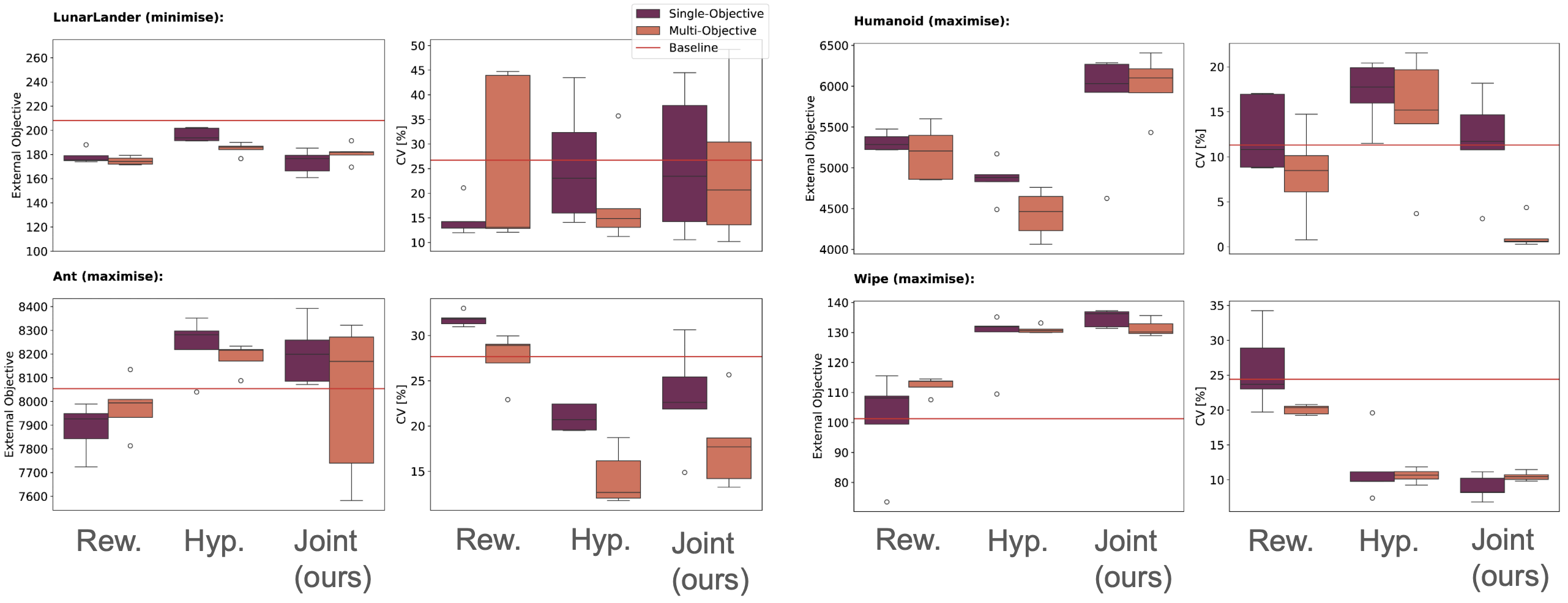

In our experiments, we compared the joint optimisation of hyperparameters and reward weights (requiring no hand-tuning!) with two alternative approaches:

- Optimising only the hyperparameters while using a competitive, pre-defined reward shape.

- Optimising only the reward weights while keeping the hyperparameters fixed at competitive baseline values.

In the paper, we used the PPO and SAC algorithms across four environments: LunarLander, Google Brax Ant, Google Brax Humanoid, and Robosuite Wipe. Among these, Robosuite Wipe stands out as a complex, underexplored environment with a challenging reward structure, making it an excellent testbed for evaluating the generalisability of our approach.

We tested two optimisation strategies:

- Single-objective optimisation, which focuses solely on maximising performance.

- Multi-objective optimisation, which balances performance and stability by optimising the performance minus the policy’s standard deviation.

The SAC results, as summarised in Figure 3, demonstrated that joint optimisation consistently matched or outperformed the hand-tuned baselines. In simpler environments like LunarLander and Ant, joint optimisation reliably recovered baseline performance without requiring any manual tuning. In more challenging environments, such as Humanoid and Wipe, joint optimisation went a step further, yielding superior performance. For instance, in the Wipe environment, the method achieved a reward score close to the theoretical maximum of 141, showing its ability to handle complex reward structures and extract maximum potential from the task.

The multi-objective optimisation further enhanced the utility of joint optimisation by improving the stability of the learned policies. While maintaining a similar level of average performance, this approach significantly reduced the variance in performance across training runs in many cases. Such consistency is crucial for real-world applications, where reliable policy behaviour can be as important as achieving peak performance.

Finally, we found that joint optimisation comes with minimal computational overhead, meaning its benefits are essentially free!

Implications and Future Directions

Our findings have broad implications for RL research and applications:

- Unified Optimisation: Hyperparameters and reward shapes should always be optimised jointly to account for their interdependencies.

- Practicality: Our approach integrates easily into existing optimisation pipelines and scales effectively to new environments.

- Generalisability: The method is robust across diverse benchmarks, including less-studied environments like Wipe, making it suitable for real-world applications.

Future research needs to extend this work by exploring more sophisticated reward function transformations and investigating the trade-off between performance and stability in RL training.

More information about this work and implementation details can be found in the paper’s GitHub repository here and the paper here.